In her 2017 book Black Tudors: The Untold Story Miranda Kaufmann has written a seminal work which challenges the idea that the horrors of late 17th and 18th Century slavery marked the beginning of Africans’ presence in England, exploitation and discrimination their only experience. The book takes the form of ten vivid and wide-ranging true-life stories, sprinkled with dramatic vignettes and specific details that bring each character to life. |

|

A wealthy Moor |

Africans were already known to have been living in Roman Britain as soldiers, slaves or even free men and women. Kaufmann shows that, by Tudor times, some were also present at the royal courts of Henry VII, Henry VIII, Elizabeth I and James I, and even in the households of courtiers like Sir Walter Raleigh and William Cecil. It is clear that real change came in William Shakespeare himself wrote several black parts - indeed, two of his greatest characters are black - and the fact that he put them into mainstream entertainment reflects the fact that they were a significant element in the population of London. Their numbers ran to many hundreds, probably more, and they were employed widely, in roles such as domestic servants, professional businessmen, musicians, dancers and entertainers. And to be clear: they were not slaves. Indeed in English law, it was not possible for anyone to be a slave in England itself (although that principle had to be re-stated in the anti-slave trade court cases of the late 18th Century because, as we know, this legal principle was certainly not adhered to in the West Indian Colonies). But in Elizabeth's reign, the black people of London actually were free; some, both men and women, married native English people. Some were given costly, high status, Christian funerals, with bearers and fine black cloth, a mark of the esteem in which they were held by employers, neighbours and fellow workers. In 1597, for example, Mary Fillis, a 20-year old black woman, had, for a long while, been the servant of a widow called Barker in Mark Lane in the City of London. She was the daughter of a Moorish shovel-maker and basket-maker and had been in England 13 or 14 years. Never christened, she became the servant of Millicent Porter, a seamstress living in East Smithfield, and now "taking some howld of faith in Jesus Chryst, was desyrous to becom a Christian, Wherefore shee made sute by hir said mistres to have some conference with the Curat". Examined in her faith by the vicar of St Botolph's, and "answering him verie Christian lyke", she did her catechisms, said the Lord's Prayer, and was baptised on Friday 3 June 1597 in front of the congregation. Among her witnesses was a group of five women, mostly wives of leading parishioners. Now a "lyvely member" of the church in Aldgate, there is no question from this description but that Mary belonged to a community with many friends and supporters |

|

Kaufmann's book also shows us that black Tudors lived and worked at many levels of society, often away from the sophistication and patronage of court life. For example, a West African man called Dederi Jaquoah, who spent two years living with an English merchant, and became a sailor who circumnavigated half the globe with Sir Francis Drake. And the wonderfully named Reasonable Blackman, a Southwark silk weaver whose silk products could easily have been traded in the City of London by members of the Haberdashers' Company, amongst others. Indeed as Kaufmann points out, Reasonable Blackman was not the only independent African businessman who was working in the cloth industry of Tudor London. Some thirty years earlier, in the reign of Queen Mary, Elizabeth's older, Catholic half-sister, 'there was a Negro [who] made fine spanish needles in Cheapside [the heart of the Mercery where Haberdashers had many shops that sold needles] but would never teach his Art to any [as it was a trade secret only he knew]'. Like silk weaving, 'Spanish needles', which were fine sewing needles made of steel, were new to England at that time |

John Blanke Trumpeter for Henry VII & VIII |

|

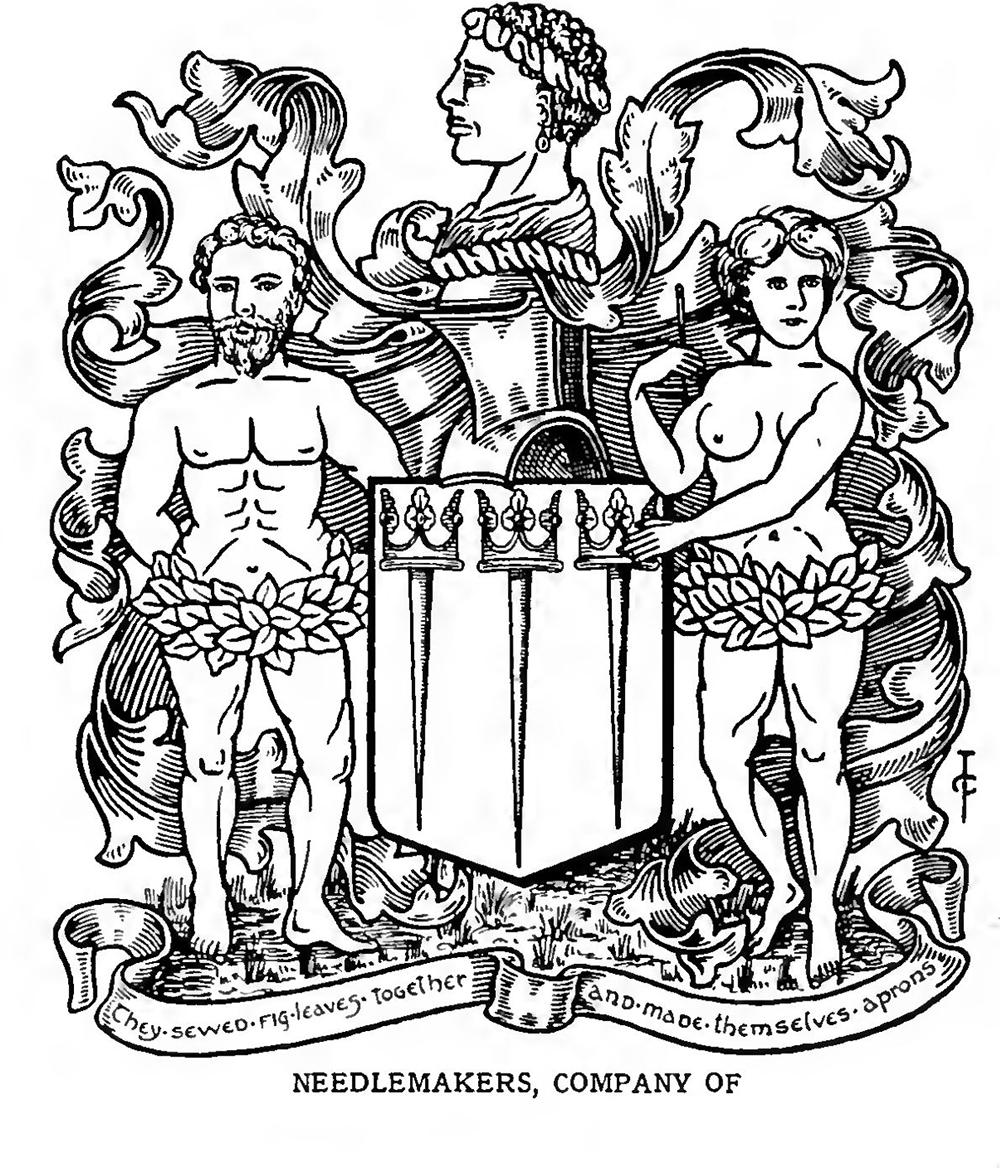

A reference to this innovative African needle-maker can actually be found in the 1780 Arms of the Worshipful Company of Needlemakers. It shows a bust of a Negro in profile with a red and silver wreath about his head, silver on his shoulders and a pearl earring. This is an allusion to the black man in Cheapside who first brought the art of steel needle-making to England. |

|

Needleworkers Arms in Use 1780 - 1915 |

|

Despite Kaufmann’s research, it is hard not to think that black people were considered as somewhat exotic figures in Tudor England. She observes, “We need to return to England as it was at the time, an island nation on the edge of Europe with not much power, a struggling Protestant nation in perpetual danger of being invaded by Spain and being wiped out. It’s about going back to before the English got involved in slave trading, before they had major colonies. The English colonial project only really gets going in the middle of the 17th century.” That said, she does leave a stark question hanging in the air: “How did we go from this period of relative acceptance to becoming the biggest slave trading nation in Europe?” In fact Black Tudors were socially no worse off than white ones. At a basic level, they were acknowledged as citizens rather than treated as outcasts. She observes, “It’s enormously significant, given how important religion was, that Africans were being baptised and married and buried within church life. It’s a really significant form of acceptance, particularly the baptism ritual, which states that ‘through baptism you are grafted into the community of God’s holy church’, in which we are all one body.” Kaufmann laments the scarcity of complete historical evidence for black lives in the Tudor period: “I wish they had kept diaries or preserved letters. Much as I’ve pieced together these lives, they’re not satisfying biographies where we know everything – more often, they are snapshots of moments.” Dr David BartleCompany Archivist |